Rain-soaked round of golf inspires ingenious Aussie Gordon Withnall

Washouts, in any sport, are invariably boring non-events. This one was a controversy. There had been many frustrated attempts to eliminate rain’s effect on our outdoor games over the last 150 years, but this was something else. Aussies who witnessed it still can’t believe it happened. It was the Fifth Test of the Ashes series, 1968. The Oval. On day five, the English had Australia on the ropes at 5-88. Then, over the lunch break, the skies dumped several centimetres of rain.

Cricket has always been subject to the vagaries of weather and other environmental conditions. Unlike other sports, it even integrates these conditions into the game itself. The Australian team was right to hope it would benefit from good old Pommy precipitation and escape with a drawn match. The Aussies settled in the dressing room. The outfield began to resemble a lake.

The English, not wishing to release their death grip, were anxious, in the face of impossible odds, to resume as soon as possible. So were their fans. To this day, Australians still don’t seem to know whether what happened next should have been allowed.

Motivated by patriotic duty, spectators splashed over the fence once the torrent ceased, trousers rolled, dresses hitched, wielding brooms, blankets and towels. In an extraordinary display of extended teamwork, provincial heroism, something, they worked industriously to remove the water. The Aussies looked on incredulously. Play resumed. With five minutes to go in the match, Derek Underwood, unplayable in the conditions, bowled the Poms to a win.

This might have been a unique event, but cricket isn’t alone in its vulnerability to rain. The Super Sopper has greatly reduced its influence – and, thankfully, removed all doubt as to how it should be dealt with.

The problem once with rain delays was that they were not confined to the actual period of precipitation. We had to hope, often against hope, that brilliant sunshine would do the job of drying things out. On courts, courses and pitches all around the world, delays often extended indefinitely, and cancellation often followed.

The beginning of change came in 1974, when Aussie inventor Gordon Withnall played a round of golf following a torrential storm. His ball landed in a large puddle. After a barb from his playing partner along the lines of, “C’mon mate, you’re supposed to be an inventor. Invent a way to get rid of this water,” he decided that indeed the time had come. Withnall was a tireless problem-solver who’d invented useful gadgets from an early age. At seven, he played a hand in the development of the first skateboard, somehow used in the pearling industry. At 12, it’s said, he came up with the world’s first electric egg incubator.

By the time he got to the 19th hole after that round of golf, Withnall had visions of a gigantic rolling sponge. According to his son, he barged into work next day and said: “Len, get some of that perforated metal lying down the back of the shed and roll it into a cylinder.”

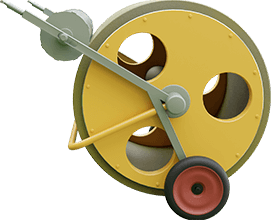

“I looked at my work-mate,” Len relates now, “and said: ‘Here we go again!’ Dad was always working on new inventions. The first one was made in three days.” It was a hand-pushed roller.

Withnall took out a worldwide patent on his “Super Sopper”. Knowing he was on a winner, he fronted the popular ABC program, The Inventors. It was invaluable publicity. Demand was almost immediate.

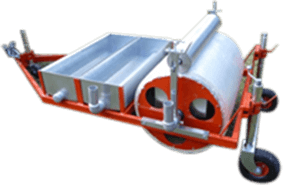

The MCC’s Ian Johnson called in 1979 and challenged him to produce a larger, customised version for drying the entire MCG. With various adjustments, including a hydraulic pump, Withnall delivered Johnson the first “Whale” Super Sopper. It consisted of two large rollers, one to absorb vast volumes of water, and another smaller one to squeeze it dry. The water collected was squirted away from the machine, discarded or re-used. The motor, drive mechanism and driver were mounted between the rollers.

Weight was distributed evenly, and the gross weight kept as low as possible, so turf would remain undamaged. To this end, Withnall employed lightweight tubing in a truss. It was the first water-removal invention to work, mainly because it squeezed water through a perforated cylinder into a holding tank.

Very soon, all Melbourne VFL clubs purchased the Whale. Racecourses demanded them. It was – ironically – Surrey CCC at The Oval in England that put in Withnall’s first overseas order. It escalated rapidly. Dozens of Japanese schools decided they were required equipment. Soon, sodden tennis courts around the world were being dried out within minutes with an adapted version.

Gordon Withnall is no longer with us, but his business, based in Australia and the USA, produces a range of powered, manual and tow-behind machines. On tennis courts, golf greens, racecourses, cricket pitches and various sports grounds around the world, regardless of the surface, the Super Sopper is standard equipment. Its constantly innovating originators continue to provide the benchmark for water removal equipment. Nature, though not entirely thwarted, has much less say in the matter.